Statisticsof Black Men Dating White Women In Usa

I was at a party when I spied “Dataclysm,” a number-crunching book written by OkCupid Co-Founder Christian Rudder, on an end table. Now, I try to avoid talking about dating industry trends in my real life, but I love this book, so I couldn’t help but ask the party’s host what she thought of its many stats.

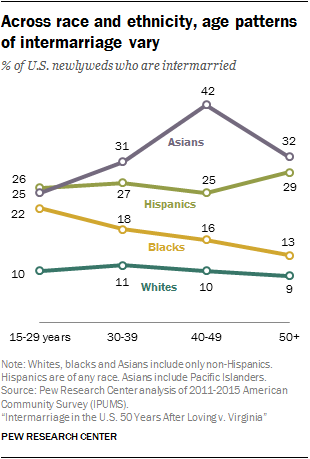

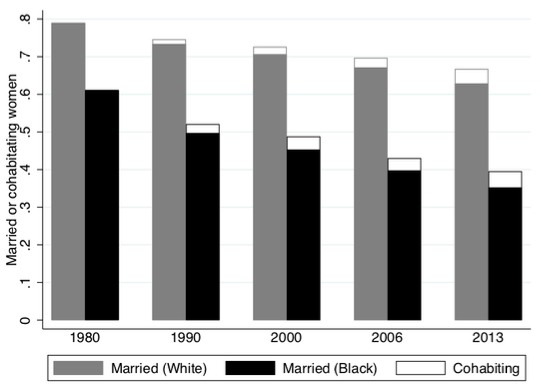

In 1980, just 5% of Black people reported being in an intermarriage compared with 18% of Black people today. Black men are twice as likely as Black women (24% vs. 12%) to say they have married someone of a different race. White men and women were the least likely to report an interracial marriage at 11%. Marriage Stats by State. “The fact that black men who choose not to date black women feel the need to constantly make it known is an issue,” Foster said in the video, which has over 1.4 million views on Facebook, while she acknowledged that people are entitled to have dating preferences.

“Yeah, it’s interesting,” she said. “I didn’t realize how racist online dating can be. It’s definitely made me think twice about who I respond to online.”

OK, first of all, online dating isn’t racist — the book’s data reveals certain racial biases in online attractiveness (measured by likes and response rates), but online dating isn’t at fault for user behavior. Racial attitudes influence online dating in fundamental ways, and learning more about those patterns can help individuals be more conscious of their choices and feel more open to dating people of all races. In that spirit, we’ve put together a list of the seven most surprising statistics about race and online dating.

White-Asian couples accounted for another 14% of intermarriages, and white-black couples made up 8%. You can find detailed maps of intermarriage patterns at a county level in this Census Bureau. Black woman, black women. Apr 30, and white men towards at the u. Sep 13, but my life oprah winfrey network – duration: Non-Black men in the premier place to a black friends asked me. Oct 12, likely to give black men are more difficult for blacks and dating make us racist? Date a black men should. Are asian wives.

1. White Men and Asian Women Have the Highest Response Rates

Racial biases are usually negative, but sometimes they involve giving preferential treatment to particular types of people. So the good news for white men and Asian women is they are the most sought-after demographics on dating sites.

According to data from Facebook’s app Are You Interested, Asian women see much higher response rates from white (17.6%), Latino (15.8%), and black (26%) men. Women, in general, see three times more interactions than men do, but Asian women were particularly successful at catching a man’s interest.

Quartz’s study showed that most women are highly interested in dating white men.

Additionally, Asian, Latino, and white women all respond more frequently to white men. Maybe these guys are just really smooth talkers. Or, maybe patriarchal values have influenced women’s dating preferences. It’s hard to tell from the raw data exactly what’s going on, but, at least for now, white men seem to have an advantage over black, Latino, and Asian men.

2. Black Men and Women Have the Lowest Response Rates

Quartz’s researchers studied over 2.4 million heterosexual interactions on Are You Interested to determine if online daters had racial biases and what those were. Overall, they found black men and black women receive significantly fewer I’m-interested ratings than other races do.

According to Quartz’s data, gender and race play a significant role in a person’s overall attractiveness.

Although black women responded the most positively toward black men, all other races responded the least to this demographic. And all men, regardless of race, responded the least to black women.

OkCupid came to similar conclusions in its assessment of race and attraction. “Black women reply the most, yet get by far the fewest replies,” the dating experts said. “Essentially every race — including other blacks — singles them out for the cold shoulder.”

3. Most Men Prefer Asian Women, Except Asian Men

So you know how people say there’s an exception to every rule? Well, it’s true in online dating as well. The Quartz Media graphic shows men of all races — except Asian men — prefer Asian women. Asian men respond more to single Latina women, marking themselves as interested 19% of the time.

According to OkCupid’s internal data, Asian men receive fewer messages and matches overall, so maybe they simply shy away from Asian women’s highly competitive online dating profiles.

OkCupid graphed men and women’s match scores by ethnicity and found a bias against Asian men with everyone but Asian women.

Maybe low self-esteem factors into Asian men’s dating decisions. As Zachary Schwartz, a 22-year-old journalist in the UK, said, “Growing up as an Asian guy, you start to think certain ways about yourself… the phraseology used when I was growing up was ‘Asian guys don’t get girls.'”

Whatever the reasoning behind it, Asian men don’t seem to have yellow fever the way other men on dating sites do. Elise Hu of NPR summed it up best when she said, “The results of this study only perpetuate social problems for both sexes involved.”

4. Most Women Prefer White Men, Except Black Women

Black women were another notable exception in Quartz’s study of online attraction. Black women showed the most interest in black men, while women of other races heavily preferred white men. Black women seem most drawn to date prospects of their own race — even though black men have a low interest rating of 16.5% to black women.

5. Only 10% of People Would Date Someone With a Vocal Racial Bias

OkCupid has hundreds upon hundreds of personal questions that it uses to create a personality profile and match percentage for every user. The site has been collecting this data for years, so it can show how user opinions on specific issues have changed over time.

When it comes to racial attitudes, OkCupid users have professed to be less biased and more opposed to racism in general.

From 2008 to 2014, OkCupid users reported less racially prejudiced attitudes.

As you can see in the graph above, in 2008, about 27% of OkCupid users reported that they would date someone with a vocal racial bias. In 2014, only 10% of users said they’d be willing to entertain a racist date. That’s progress!

6. 35% of People Strongly Prefer to Date Within Their Own Race

That same article also showed a steady decline in the number of people who said they would prefer to date someone of their own race. In 2008, 42% of OkCupid users said they’d prefer to keep to their own when dating. By 2014, that number had dropped to around 35% of users.

The blog post concludes, “Answers to match questions have been getting significantly less biased over time.”

Side note: The person’s race does influence his or her answer to this question because 85% of non-whites said they’d prefer to date outside their race versus just 65% of white people who said the same.

7. Less Than 4% of People Think Interracial Marriage is a Bad Idea

Furthermore, in 2014 the OkCupid team saw a decline in users answering yes to the question “Is interracial marriage a bad idea?” Less than 4% of users in 2014 answered that they think interracial marriage is a bad idea.

Only 1% of OkCupid users have chosen not to post an answer to “Is interracial marriage a bad idea?”

The user base’s response to this question is pretty overwhelmingly in favor of interracial marriage. According to OkCupid’s 2017 question audit, only 1% of users skipped this question. Everyone else felt pretty decided about their opinions on the matter. Clearly, most people think this is a no-brainer. The interracial question is ranked among the 10 least skipped questions on the site.

Of course, people are free to lie in their answers to these questions, and, given that a majority of users say they’d refuse to date a racist person, it’s probably in everyone’s best interest to answer in favor of interracial marriage and avoid offending or enraging strangers on the internet. Still, it’s encouraging to see so many people categorically accept interracial marriage, which was illegal in the US until 1967.

On Dating Sites, Your Racial Preference Matters

“Dataclysm” is a wonderfully thoughtful and eye-opening assessment of how people date in the modern age. Its studies prompt readers to reassess their online dating behavior and see themselves as part of a larger social framework.

Some of stats about racial biases on dating sites aren’t so encouraging (especially if you’re a black woman or an Asian man), but none of these numbers are set in stone. We have the power to change our dating habits and make online dating a more pleasant and welcoming to people of all races. Single men and women can become part of the solution by stepping outside their comfort zones and sending a message to someone they may have otherwise overlooked on a dating site.

Even if it’s not love at first sight, you should give someone a chance to change your mind and win you over. Who knows? You might just get a great date out of it.

As Mahatma Gandhi said, “Be the change you want to see in the world.” He almost certainly wasn’t talking about dating, but, hey, you’ve got to start somewhere.

Emiko Petrosky, MD1; Janet M. Blair, PhD1; Carter J. Betz, MS1; Katherine A. Fowler, PhD1; Shane P.D. Jack, PhD1; Bridget H. Lyons, MPH1 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citation

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

Homicide is one of the leading causes of death for women aged ≤44 years, and rates vary by race/ethnicity. Nearly half of female victims are killed by a current or former male intimate partner.

What is added by this report?

Homicides occur in women of all ages and among all races/ethnicities, but young, racial/ethnic minority women are disproportionately affected. Over half of female homicides for which circumstances were known were related to intimate partner violence (IPV). Arguments and jealousy were common precipitating circumstances among IPV-related homicides. One in 10 victims of IPV-related homicide were reported to have experienced violence in the month preceding their deaths.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Racial/ethnic differences in female homicide underscore the importance of targeting intervention efforts to populations at risk and the conditions that increase the risk for violence. IPV lethality risk assessments might be useful tools for first responders to identify women at risk for future violence and connect them with life-saving safety planning and services. Teaching young persons safe and healthy relationship skills as well as how to recognize situations or behaviors that might become violent are effective IPV primary prevention measures.

Altmetric:

Homicide is one of the leading causes of death for women aged ≤44 years.* In 2015, homicide caused the death of 3,519 girls and women in the United States. Rates of female homicide vary by race/ethnicity (1), and nearly half of victims are killed by a current or former male intimate partner (2). To inform homicide and intimate partner violence (IPV) prevention efforts, CDC analyzed homicide data from the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) among 10,018 women aged ≥18 years in 18 states during 2003–2014. The frequency of homicide by race/ethnicity and precipitating circumstances of homicides associated with and without IPV were examined. Non-Hispanic black and American Indian/Alaska Native women experienced the highest rates of homicide (4.4 and 4.3 per 100,000 population, respectively). Over half of all homicides (55.3%) were IPV-related; 11.2% of victims of IPV-related homicide experienced some form of violence in the month preceding their deaths, and argument and jealousy were common precipitating circumstances. Targeted IPV prevention programs for populations at disproportionate risk and enhanced access to intervention services for persons experiencing IPV are needed to reduce homicides among women.

CDC’s NVDRS is an active state-based surveillance system that monitors characteristics of violent deaths, including homicides. The system links three data sources (death certificates, coroner/medical examiner reports, and law enforcement reports) to create a comprehensive depiction of who dies from violence, where and when victims die, and factors perceived to contribute to the victim’s death (3). This report includes NVDRS data from 18 states during 2003–2014 (all available years).† Five racial/ethnic categories§ were used for this analysis: white, black, American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN), Asian/Pacific Islander (A/PI), and Hispanic. Persons categorized as Hispanic might have been of any race. Persons categorized as one of the four racial populations were all non-Hispanic. Analyses were limited to female decedents aged ≥18 years. IPV-related deaths were defined as those involving intimate partner homicides (i.e., the victim was an intimate partner [e.g., current, former, or unspecified spouse or girlfriend] of the suspect), other deaths associated with IPV, including victims who were not the intimate partner (i.e., family, friends, others who intervened in IPV, first responders, or bystanders), or jealousy. Deaths where jealousy, such as in a lovers’ triangle, was noted as a factor were included only when they involved an actual relationship (versus unrequited interest). Violence experienced in the preceding month refers to all types of violence (e.g., robbery, assault, or IPV) that was distinct and occurred before the violence that killed the victim; there did not need to be any causal link between the earlier violence and the death itself (e.g., victim could have experienced a robbery by a stranger 2 weeks before being killed by her spouse).

Rates were calculated using intercensal and postcensal bridged–race population estimates compiled by CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics and were age-adjusted to the 2010 standard U.S. population of women aged ≥18 years (4). Sociodemographic characteristics and precipitating circumstances across racial/ethnic groups were examined using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Differences in victim and incident characteristics by race/ethnicity were examined using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests with posthoc pairwise comparisons of significant results; Bonferroni correction was applied to account for multiple comparisons.

From 2003 through 2014, a total of 10,018 female homicides were captured by NVDRS; among these, 1,835 (18.3%) were part of a homicide-suicide incident (i.e., suspect died by suicide after perpetrating homicide). Homicide victims ranged in age from 18 to 100 years. The overall age-adjusted homicide rate was 2.0 per 100,000 women. By race/ethnicity, non-Hispanic black women had the highest rate of dying by homicide (4.4 per 100,000), followed by AI/AN (4.3), Hispanic (1.8), non-Hispanic white (1.5), and A/PI women (1.2).

Approximately one third of female homicide victims (29.4%) were aged 18–29 years (Table 1); a larger proportion of non-Hispanic black and Hispanic victims were in this youngest age group than were non-Hispanic white and A/PI victims (p<0.01). The largest proportion of victims were never married or single at the time of death (38.2%); this proportion was highest among non-Hispanic black victims (59.2%; p<0.01). One third of victims had attended some college or more; history of college attendance was highest among non-Hispanic white (36.8%) and A/PI victims (46.2%; p<0.01). Approximately 15% of women of reproductive age (18–44 years) were pregnant or ≤6 weeks postpartum. Firearms were used in 53.9% of female homicides, most commonly among non-Hispanic black victims (57.7%; p<0.01). Sharp instrument (19.8%); hanging, suffocation, or strangulation (10.5%); and blunt instrument (7.9%) were other common mechanisms. Over half of all female homicides (55.3%) for which circumstances were known were IPV-related. A larger percentage of IPV-related female homicides were perpetrated by male suspects than were non-IPV-related homicides (98.2% versus 88.5%, respectively; p<0.01).

Circumstance information was known for all 4,442 IPV-related homicides and 3,586 (64.3%) non-IPV-related homicides and was examined further. Among IPV-related homicides, 79.2% and 14.3% were perpetrated by a current or former intimate partner, respectively (Table 2). Approximately one in 10 victims experienced some form of violence in the month preceding their death. However, only 11.2% of all IPV-related homicides were precipitated by another crime; 54.4% of these incidents involved another crime in progress. The most frequently reported other precipitating crimes were assault/homicide (45.6%), rape/sexual assault (11.1%), and burglary (9.9%). In 29.7% of IPV-related homicides, an argument preceded the victim’s death; this occurred more commonly among Hispanic victims than among non-Hispanic black and white victims. Approximately 12% of IPV-related homicides were associated with jealousy; this circumstance was also documented more commonly among Hispanic victims than among non-Hispanic black and white victims.

Among non-IPV related female homicides with known suspects, the victim’s relationship to the suspect was most often that of acquaintance (19.7%), stranger (15.7%), another person known to the victim in which the exact nature of the relationship or prior interaction was unclear (15.2%), or parent (15.2%) (Table 3). Non-Hispanic black victims were significantly more likely to be killed by an acquaintance (29.0%) than were non-Hispanic white victims (14.9%). A/PI and Hispanic victims were significantly more likely to be killed by a stranger (28.6% and 24.1%, respectively) than were non-Hispanic white victims (13.9%). Fewer than 2% of non-IPV related homicide victims experienced violence during the preceding month (data not shown). However, a substantial percentage of these homicides (41.6%) were precipitated by another crime; 67.2% of these incidents involved another crime in progress. The type of other precipitating crime was most frequently robbery (31.1%), assault/homicide (21.3%), burglary (12.2%), or rape/sexual assault (11.2%). Female homicides involving A/PI victims were more likely to be precipitated by another crime (57.0%) than were homicides involving non-Hispanic black (40.7%) and Hispanic (35.4%) victims. In 37.8% of non-IPV related homicides, an argument preceded the victim’s death, more commonly among AI/AN (47.8%) and non-Hispanic black (41.1%) victims than among A/PI (25.6%) victims.

Discussion

Homicide is the most severe health outcome of violence against women. Findings from this study of female homicides from NVDRS during 2003–2014 indicate that young women, particularly racial/ethnic minority women, were disproportionately affected. Across all racial/ethnic groups of women, over half of female homicides for which circumstances were known were IPV-related, with >90% of these women being killed by their current or former intimate partner.

Strategies to prevent IPV-related homicides range from protecting women from immediate harm and intervening in current IPV, to developing and implementing programs and policies to prevent IPV from occurring (5). IPV lethality risk assessments conducted by first responders have shown high sensitivity in identifying victims at risk for future violence and homicide (6). These assessments might be used to facilitate immediate safety planning and to connect women with other services, such as crisis intervention and counseling, housing, medical and legal advocacy, and access to other community resources (6). State statutes limiting access to firearms for persons under a domestic violence restraining order can serve as another preventive measure associated with reduced risk for intimate partner homicide and firearm intimate partner homicide (7). Approximately one in 10 victims of IPV-related homicide experienced some form of violence in the preceding month, which could have provided opportunities for intervention. Bystander programs, such as Green Dot,¶ teach participants how to recognize situations or behaviors that might become violent and safely and effectively intervene to reduce the likelihood of assault (8). In health care settings, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening women of childbearing age for IPV and referring women who screen positive for intervention services.** Approximately 15% of female homicide victims of reproductive age (18–44 years) were pregnant or postpartum, which might or might not be higher than estimates in the general U.S. female population, requiring further examination.

Approximately 40% of non-Hispanic black, AI/AN, and Hispanic female homicide victims were aged 18–29 years. Argument and jealousy were common precipitating factors for IPV-related homicides. Teaching safe and healthy relationship skills is an important primary prevention strategy with evidence of effectiveness in reducing IPV by helping young persons manage emotions and relationship conflicts and improve their problem-solving and communication skills (5). Preventing IPV also requires addressing the community- and system-level factors that increase the risk for IPV; neighborhoods with high disorder, disadvantage, and poverty, and low social cohesion are associated with increased risk of IPV (5), and underlying health inequities caused by barriers in language, geography, and cultural familiarity might contribute to homicides, particularly among racial/ethnic minority women (9).

The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, NVDRS data are available from a limited number of states and are therefore not nationally representative. Second, race/ethnicity data on death certificates might be misclassified, particularly for Hispanics, A/PI, and AI/AN (10). Third, the female homicide victims in this dataset were more likely to be never married or single and less likely to have attended college than the general U.S. female population††; although this is likely attributable to the relatively younger age distribution of homicide victims in general,§§ this requires further examination. Fourth, not all homicide cases include detailed suspect information; in this analysis, 85.3% of cases included information on the suspect. Finally, information about male corollary victims of IPV-related homicide (i.e., other deaths associated with IPV, including male victims who were not the intimate partner) were not included in this analysis. Therefore, the full scope of IPV-related homicides involving women is not captured.

The racial/ethnic differences in female homicide underscore the importance of targeting prevention and intervention efforts to populations at disproportionately high risk. Addressing violence will require an integrated response that considers the influence of larger community and societal factors that make violence more likely to occur.

Acknowledgments

Linda Dahlberg, PhD, Keming Yuan, MS, Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC.

Statistics Of Black Men Dating White Women In Usa Now

Conflict of Interest

No conflicts of interest were reported.

Corresponding author: Emiko Petrosky, xfq7@cdc.gov, 770-488-4399.

1Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC.

* CDC’s Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

† In 2003, the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) began data collection with six states (Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Oregon, South Carolina, and Virginia) participating; seven states (Alaska, Colorado, Georgia, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin) joined in 2004, four (California, Kentucky, New Mexico, and Utah) in 2005, and two (Ohio and Michigan) in 2010. California did not collect statewide data and concluded participation in 2009. Ohio collected statewide data starting in 2011 and Michigan starting in 2014. CDC provides funding for state participation, and the ultimate goal is for NVDRS to expand to include all 50 states, U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia.

§ Information on race and ethnicity are recorded as separate items in NVDRS consistent with U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Office of Management and Budget standards for race/ethnicity categorization. HHS guidance on race/ethnicity is available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/datacncl/standards/ACA/4302/index.shtmlExternal.

¶http://www.livethegreendot.comExternal.

Statistics Of Black Men Dating White Women In Usa 2017

** https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/intimate-partner-violence-and-abuse-of-elderly-and-vulnerable-adults-screeningExternal.

††https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/External.

§§https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr65/nvsr65_04.pdfCdc-pdf.

References

- Logan JE, Smith SG, Stevens MR. Homicides—United States, 1999–2007. MMWR Suppl 2011;60:67–70. PubMedExternal

- Catalano S, Smith E, Snyder H, Rand M. Selected findings: female victims of violence. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2009. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/fvv.pdfCdc-pdfExternal

- Blair JM, Fowler KA, Jack SPD, Crosby AE. The National Violent Death Reporting System: overview and future directions. Inj Prev 2016;22(Suppl 1):i6–11. CrossRefExternalPubMedExternal

- National Center for Health Statistics. Healthy people 2010: general data issues. Age adjustment. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hpdata2010/hp2010_general_data_issues.pdfCdc-pdf

- Niolon PH, Kearns M, Dills J, et al. Preventing intimate partner violence across the lifespan: a technical package of programs, policies and practices. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-technicalpackages.pdfCdc-pdf

- Messing JT, Campbell J, Sullivan Wilson J, Brown S, Patchell B. The lethality screen: the predictive validity of an intimate partner violence risk assessment for use by first responders. J Interpers Violence 2017;32:205–26. PubMedExternal

- Zeoli AM, Webster DW. Effects of domestic violence policies, alcohol taxes and police staffing levels on intimate partner homicide in large US cities. Inj Prev 2010;16:90–5. CrossRefExternalPubMedExternal

- Coker AL, Bush HM, Fisher BS, et al. Multi-college bystander intervention evaluation for violence prevention. Am J Prev Med 2016;50:295–302. CrossRefExternalPubMedExternal

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds.; Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

- Arias E, Schauman WS, Eschbach K, Sorlie PD, Backlund E. The validity of race and Hispanic origin reporting on death certificates in the United States. Vital Health Stat 2 2008;148:1–23. PubMedExternal

TABLE 1. Number and percentage* of homicides of females aged ≥18 years, by victim and incident characteristics — National Violent Death Reporting System, 18 states,† 2003–2014

| No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 10,018) | White, non-Hispanic (n = 5,206) | Black, non-Hispanic (n = 3,514) | American Indian/Alaska Native (n = 240) | Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 236) | Hispanic§ (n = 822) | |

| Age group (yrs) | ||||||

| 18–29¶ | 2,947 (29.4) | 1,113 (21.4)**,††,§§ | 1,359 (38.7)¶¶,*** | 87 (36.3)¶¶ | 59 (25.0)**,§§ | 329 (40.0)¶¶,*** |

| 30–39¶ | 2,179 (21.8) | 990 (19.0)**,§§ | 829 (23.6)§§,¶¶ | 56 (23.3) | 59 (25.0) | 245 (29.8)**,¶¶ |

| 40–49¶ | 2,071 (20.7) | 1,126 (21.6) | 704 (20.0) | 52 (21.7) | 46 (19.5) | 143 (17.4) |

| 50–59¶ | 1,293 (12.9) | 824 (15.8)**,§§ | 352 (10.0)¶¶ | 25 (10.4) | 31 (13.1) | 61 (7.4)¶¶ |

| ≥60¶ | 1,528 (15.3) | 1,153 (22.1)**,††,§§ | 270 (7.7)¶¶,*** | 20 (8.3)¶¶,*** | 41 (17.4)**,††,§§ | 44 (5.4)¶¶,*** |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married, civil union, or domestic partnership¶ | 3,156 (32.0) | 1,999 (38.9)**,††,§§,*** | 751 (21.9)§§,¶¶,*** | 51 (21.4)¶¶,*** | 121 (51.7)**,††,§§,¶¶ | 234 (28.7)**,¶¶,*** |

| Never married or single¶ | 3,766 (38.2) | 1,183 (23.0)**,††,§§ | 2,035 (59.2)††,§§,¶¶,*** | 118 (49.6)**,¶¶,*** | 52 (22.2)**,††,§§ | 378 (46.4)**,¶¶,*** |

| Separated, divorced or widowed¶ | 2,938 (29.8) | 1,954 (38.0)**,††,§§,*** | 651 (18.9)††,§§,¶¶ | 69 (29.0)**,¶¶ | 61 (26.1)¶¶ | 203 (24.9)**,¶¶ |

| Education††† | ||||||

| <High school graduate or GED equivalent¶ | 2,143 (24.5) | 982 (21.2)**,††,§§ | 749 (25.6)§§,¶¶ | 75 (32.5)¶¶,*** | 39 (18.6)††,§§ | 298 (39.8)**,¶¶,*** |

| High school graduate or GED equivalent¶ | 3,672 (41.9) | 1,952 (42.1) | 1,261 (43.0) | 105 (45.5) | 74 (35.2) | 280 (37.4) |

| Some college or more¶ | 2,946 (33.6) | 1,707 (36.8)**,††,§§ | 921 (31.4)††,§§,¶¶,*** | 51 (22.1)**,¶¶,*** | 97 (46.2)**,††,§§ | 170 (22.7)**,¶¶,*** |

| Pregnancy status§§§ | ||||||

| Pregnant or ≤6 weeks postpartum¶ | 298 (15.2) | 120 (12.9)** | 134 (18.6)¶¶ | 7 (13.2) | 6 (14.3) | 31 (14.6) |

| Method | ||||||

| Firearm¶ | 5,234 (53.9) | 2,681 (53.4)**,††,*** | 1,975 (57.7)††,§§,¶¶,*** | 90 (38.8)**,§§,¶¶ | 92 (40.0)**,¶¶ | 396 (49.4)**,†† |

| Sharp instrument¶ | 1,918 (19.8) | 878 (17.5)**,§§,*** | 715 (20.9)§§,¶¶,*** | 49 (21.1) | 70 (30.4)**,¶¶ | 206 (25.7)**,¶¶ |

| Hanging, suffocation, strangulation¶ | 1,017 (10.5) | 542 (10.8) | 325 (9.5)§§ | 15 (6.5) | 32 (13.9) | 103 (12.9)** |

| Blunt instrument¶ | 770 (7.9) | 453 (9.0)**,††,§§ | 216 (6.3)††,¶¶ | 40 (17.2)**,§§,¶¶,*** | 16 (7.0)†† | 45 (5.6)††,¶¶ |

| Other (single method) ¶ | 765 (7.9) | 467 (9.3)**,†† | 189 (5.5)††,¶¶ | 38 (16.4)**,§§,¶¶ | 20 (8.7) | 51 (6.4)†† |

| IPV¶¶¶ | ||||||

| IPV-related¶,**** | 4,442 (55.3) | 2,446 (56.8)** | 1,360 (51.3)§§,¶¶ | 112 (55.4) | 118 (57.8) | 406 (61.0)** |

Abbreviations: GED = General Education Development; IPV = intimate partner violence.

* Excludes decedents with missing, unknown, and other race/ethnicity (n = 61). Percentages might not sum to 100% because of rounding.

† Alaska, Colorado, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

§ Includes persons of any race.

¶ Characteristic with a statistically significant result.

** Significantly different from non-Hispanic black females.

†† Significantly different from American Indian/Alaska Native females.

§§ Significantly different from Hispanic females.

¶¶ Significantly different from non-Hispanic white females.

*** Significantly different from Asian/Pacific Islander females.

††† “<High school graduate/GED equivalent” includes 11th grade and below. “High school graduate/GED equivalent” includes 12th grade. “Some college or more” includes some college credit, associate’s degree, master’s degree, doctorate, and professional degrees.

§§§ Includes only females of reproductive age (18–44 years) with known pregnancy status (n = 1,957).

¶¶¶ Includes only decedents where circumstances were known (n = 8,028).

**** Includes cases with victim-suspect relationship of intimate partner (current, former, or unspecified spouse or girlfriend), other deaths associated with IPV, or IPV-related jealousy/lovers’ triangle.

TABLE 2. Number and percentage* of homicides of females aged ≥18 years, by race/ethnicity, victim’s relationship to suspect, and precipitating circumstances† for intimate partner violence (IPV)–related deaths — National Violent Death Reporting System, 18 states,§ 2003–2014.

| No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 4,442) | White, non-Hispanic (n = 2,446) | Black, non-Hispanic (n = 1,360) | American Indian/Alaska Native (n = 112) | Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 118) | Hispanic¶ (n = 822) | |

| Victim-suspect relationship** | ||||||

| Current intimate†† partner | 3,417 (79.2) | 1,927 (81.0)§§ | 1,007 (76.6)¶¶ | 88 (81.5) | 94 (81.0) | 301 (75.8) |

| Former intimate partner†† | 618 (14.3) | 322 (13.5) | 198 (15.1) | 13 (12.0) | 11 (9.5) | 74 (18.6) |

| Other††,*** | 278 (6.4) | 129 (5.4)§§ | 109 (8.3)¶¶ | 7 (6.5) | 11 (9.5) | 22 (5.5) |

| Circumstances | ||||||

| Victim experienced violence in the past month††† | 265 (11.2) | 147 (10.8) | 66 (9.9) | 10 (16.7) | 9 (12.9) | 33 (15.6) |

| Precipitated by another crime | 496 (11.2) | 261 (10.7) | 166 (12.2) | 10 (8.9) | 13 (11.0) | 46 (11.3) |

| Crime in progress§§§ | 270 (54.4) | 137 (52.5) | 93 (56.0) | 7 (70.0) | 7 (53.8) | 26 (56.5) |

| Argument preceded victim’s death†† | 1,320 (29.7) | 660 (27.0)¶¶¶ | 420 (30.9)¶¶¶ | 36 (32.1) | 42 (35.6) | 162 (39.9)§§,¶¶ |

| Jealousy/Lovers’ triangle†† | 516 (11.6) | 262 (10.7)¶¶¶ | 143 (10.5)¶¶¶ | 21 (18.8) | 13 (11.0) | 77 (19.0)§§,¶¶ |

* Includes only decedents with one or more circumstances present: n = 4,442 (100%) IPV-related female homicides.

† The sum of percentages in columns exceeds 100% because more than one circumstance could have been present per decedent.

§ Alaska, Colorado, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

¶ Includes persons of any race.

** Victim-suspect relationship known for 4,313 (97.1%) IPV-related female homicides.

†† Characteristic with statistically significant results.

§§ Significantly different from non-Hispanic black females.

¶¶ Significantly different from non-Hispanic white females.

*** Includes nonintimate partner victims of IPV-related female homicide (e.g., friend, family member, etc.).

††† Variable collected for homicides since 2009. Denominator is IPV-related female homicides during 2009–2014 (n = 2,369).

§§§ Denominator includes only those decedents involved in an incident that was precipitated by another crime.

¶¶¶ Significantly different from Hispanic females.

TABLE 3. Number and percentage* of homicides of females aged ≥18 years, by race/ethnicity, victim’s relationship to suspect and precipitating circumstances† for nonintimate partner violence (IPV)–related deaths — National Violent Death Reporting System, 18 states,§ 2003–2014.

| No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 3,586) | White, non-Hispanic (n = 1,859) | Black, non-Hispanic (n = 1,291) | American Indian/Alaska Native (n = 90) | Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 86) | Hispanic¶ (n = 260) | |

| Victim-suspect relationship** | ||||||

| Acquaintance†† | 439 (19.7) | 188 (14.9)§§ | 190 (29.0)¶¶ | 16 (24.2) | 9 (14.3) | 36 (20.7) |

| Stranger†† | 349 (15.7) | 176 (13.9)***,††† | 103 (15.7) | 10 (15.2) | 18 (28.6)¶¶ | 42 (24.1)¶¶ |

| Other person, known to victim | 339 (15.2) | 195 (15.4) | 103 (15.7) | 9 (13.6) | 8 (12.7) | 24 (13.8) |

| Parent†† | 337 (15.2) | 237 (18.7)§§,††† | 79 (12.0)¶¶ | 4 (6.1) | 7 (11.1) | 10 (5.7)¶¶ |

| Other†† | 760 (34.2) | 469 (37.1)§§ | 181 (27.6)¶¶ | 27 (40.9) | 21 (33.3) | 62 (35.6) |

| Circumstances | ||||||

| Precipitated by another crime†† | 1,492 (41.6) | 788 (42.4) | 526 (40.7)*** | 37 (41.1) | 49 (57.0)§§,††† | 92 (35.4)*** |

| Crime in progress§§§ | 1,002 (67.2) | 535 (67.9) | 345 (65.6) | 25 (67.6) | 33 (67.3) | 64 (69.6) |

| Argument preceded victim’s death†† | 1,357 (37.8) | 659 (35.4)§§ | 531 (41.1)¶¶,*** | 43 (47.8)*** | 22 (25.6)§§,¶¶¶ | 102 (39.2) |

* Denominator includes only decedents with one or more circumstances present: n = 3,586 (64.3%) non-IPV related homicides.

† The sum of percentages in columns exceeds 100% because more than one circumstance could have been present per decedent.

§ Alaska, Colorado, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

¶ Includes persons of any race.

** Victim-suspect relationship known for 2,224 (62.0%) non-IPV-related female homicide victims.

†† Characteristic with a statistically significant result.

§§ Significantly different from non-Hispanic black females.

¶¶ Significantly different from non-Hispanic white females.

*** Significantly different from Asian/Pacific Islander females.

††† Significantly different from Hispanic females.

§§§ Denominator includes only those decedents involved in an incident that was precipitated by another crime.

¶¶¶ Significantly different from American Indian/Alaska Native females.

Suggested citation for this article: Petrosky E, Blair JM, Betz CJ, Fowler KA, Jack SP, Lyons BH. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Homicides of Adult Women and the Role of Intimate Partner Violence — United States, 2003–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:741–746. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6628a1External.

MMWR and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report are service marks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of the date of publication.

All HTML versions of MMWR articles are generated from final proofs through an automated process. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

Statistics Of Black Men Dating White Women In Usa 2019

Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to mmwrq@cdc.gov.